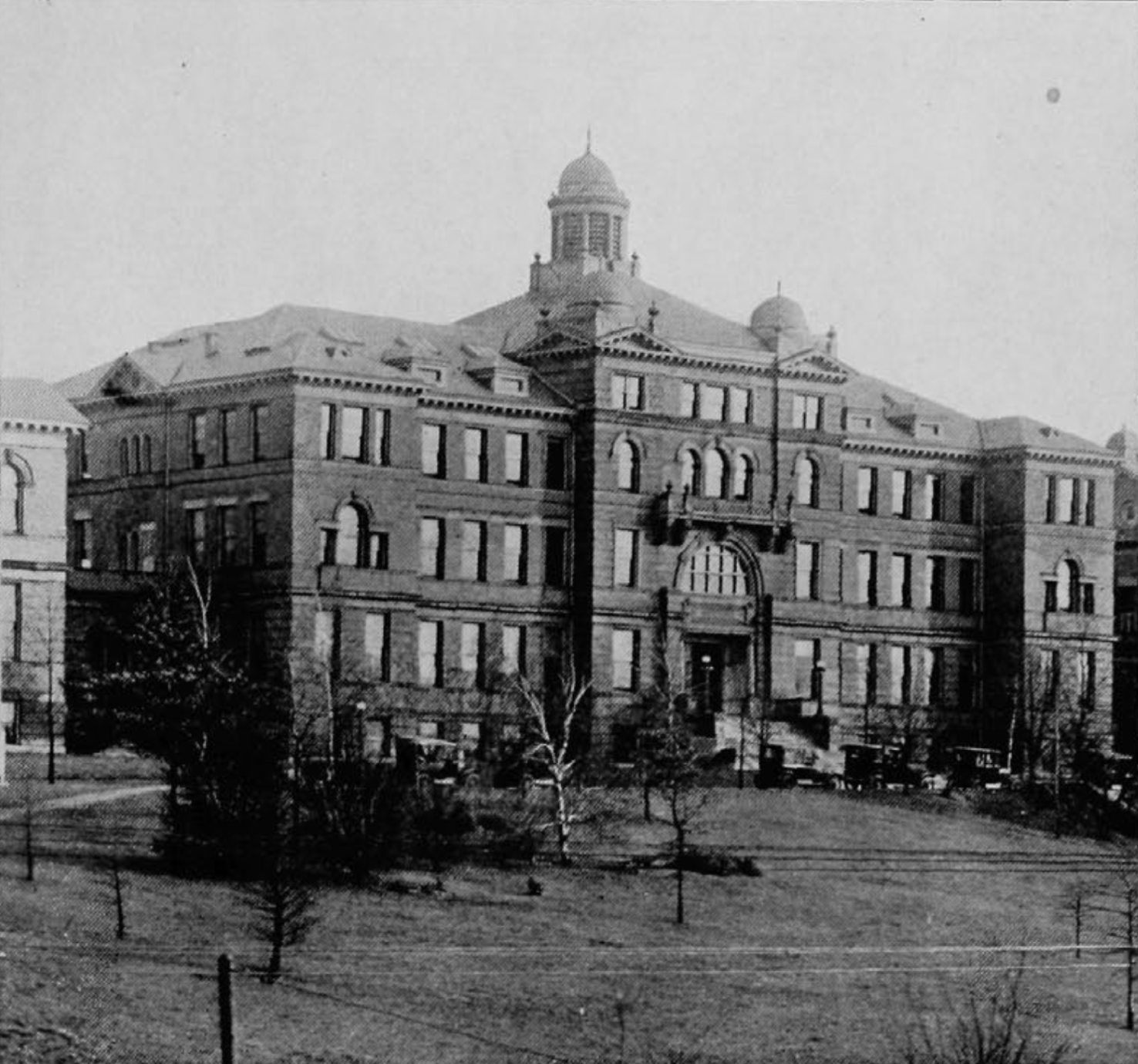

The original McMicken Hall [uc.edu]

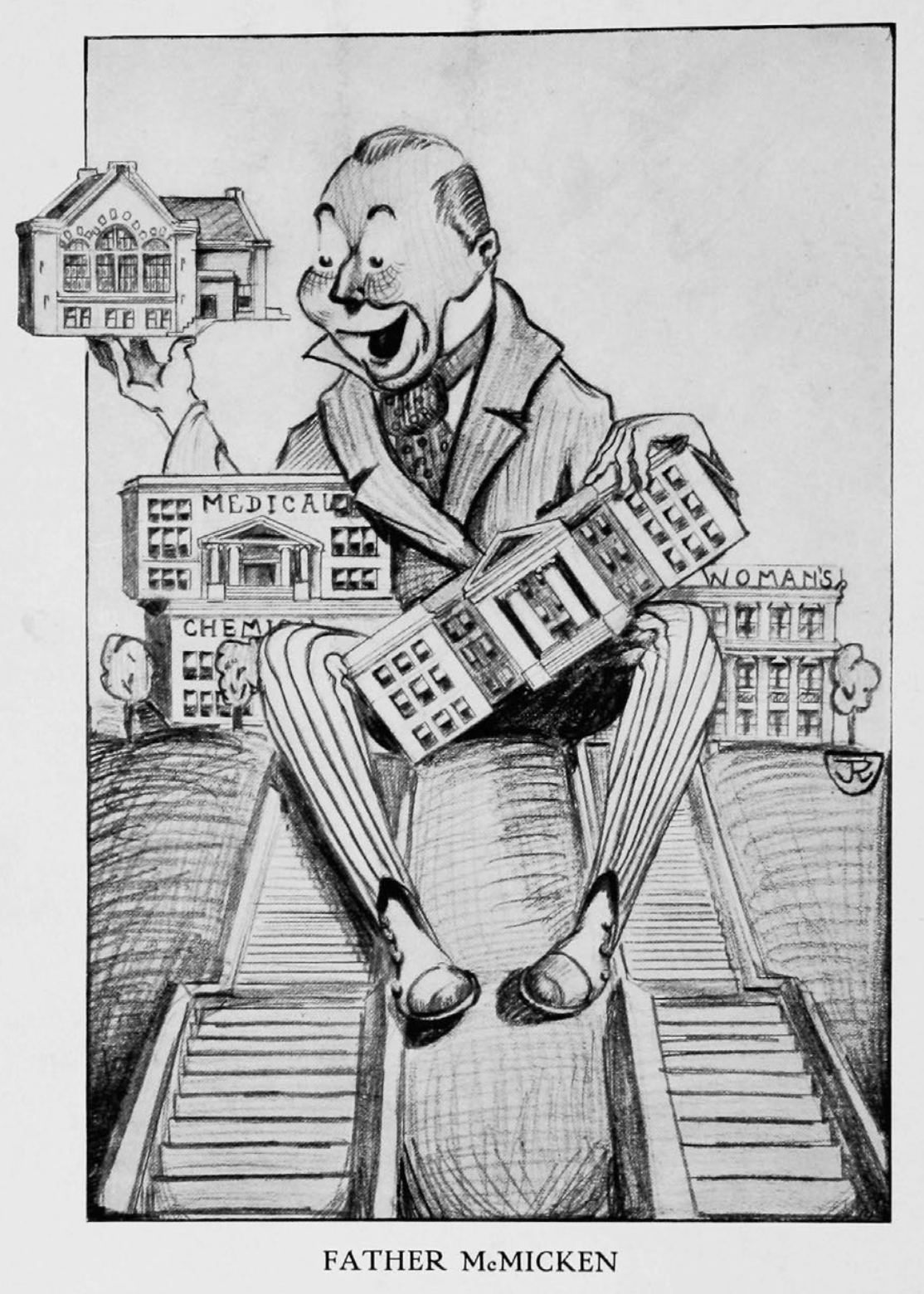

The University of Cincinnati’s early history is a winding one. While the date credited to UC’s establishment is 1819, that’s deceptive. You see, the Medical College of Ohio was founded in 1819. So was Cincinnati College. The latter only lasted six years before shuttering. It was revived in 1835 and later merged with Cincinnati Law School (this is where President William Howard Taft graduated). While all these institutions eventually melded together, the UC we know today was born in 1858 upon the death of Charles McMicken.

Read McMicken’s will. On Page 19 next to item XXXI, you’ll see it:

"Having long cherished the desire to found an institution, where white boys and girls might be taught, not only a knowledge of their duties to their Creator and their fellow men, but also receive the benefit of a sound, thorough and practical English education, and such as might fit them for the active duties of life; as well as instruction in all the higher branches of knowledge, except Denominational Theology, to the extent that the same are now, or may hereafter be taught, in any of the secular Colleges or Universities of the highest grade in the Country, I feel grateful to God that through the his kind Providence, I have been sufficiently favored to gratify the wish of my heart."

A couple of things stick out here. First off, this may be the longest sentence in the history of the English language. Second, this guy did not want his money used to educate non-whites. He was so concerned about this stipulation that he brought it up again in the next paragraph while also adding that he’d like two colleges established: One for men and one for women. (Subtext that I can’t adequately address in this article: Charles McMicken really, really, really sucked.)

(Side note: I’m not gonna get into the sliminess of Charles McMicken’s racism and sexism, but you may be wondering how long the university abided by McMicken’s wishes to fill UC with white students only. The answer is: Not very long. I'm not sure that UC ever explicitly banned black students, but they certainly looked down upon them, did not actively recruit them, and had a general understanding that any black enrollment was against the wishes of Charles McMicken. The first black student enrolled at UC in 1886. In 1893, a judge officially voided McMicken’s request to keep UC white, using the reasoning that his will simply stated that the university should be for “white boys and girls” while not explicitly excluding other races. McMicken must’ve rolled over in his grave. Following this ruling, the first black student to graduate from the university was Alice May Easton in 1897.)

In the ensuing pages of his will, we see McMicken unloading a lifetime’s worth of property into the hands of the city of Cincinnati. The previous items in his will disperse belongings to various family members (he never married and the only children he had were born of his slaves—neat!) but he essentially gives the city the rest of his stuff, including but not limited to 1,200 acres of land in Baton Rouge, 124.3 acres in Delhi Township, and a bunch of railroad bonds. The value totaled roughly $1 million. Adjusted for 2018, that’s just shy of $29 million.

Legal holdups and the Civil War delayed the official establishment of the university. In 1869 the McMicken School of Drawing and Design (later known as DAAP) was founded. The following year the city of Cincinnati combined the funds from the McMicken estate with some other government money to establish a public university. It was called McMicken University for just a month before being renamed and absorbing the design school.

The University of Cincinnati was born.

The original UC building (circled) was located on a hillside next to the Bellevue Incline, pictured here in a promotional lithograph from Christian Moerlein Brewing Co. [via uc.edu]

The version of UC that existed from 1870 to 1893 is not something that anyone living in 2018 would recognize. UC had it rough for a little bit. In 1860, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that all of McMicken’s property in that state would not belong to Cincinnati, despite the will’s intent. They didn't want to give land ownership to another state's government. To make matters worse, McMicken’s land in Cincinnati had rapidly devalued because of the expanding industrial economy. McMicken's estate, which was once a rural hillside haven located near where Bellevue Hill Park currently exists, had turned into a crappy piece of land on the fringes of Cincinnati. The will had stipulated that the two colleges (one for men and one for women) would be built on this property that was now choked by dust and soot from nearby manufacturing. Also, the land on the hillside made the school very difficult to access during the winter. UC and its board were miserable, and they made it clear. The university’s annual report published to the Cincinnati mayor in 1872 was very whiny—and for a good reason:

"From the time of Mr. McMicken’s decease, and the promulgation of his will, bestowing the estate upon the city for the establishment of 'two Colleges for the education of white boys and girls,' there has been a general but ill-founded impression that an institution of learning, in all its branches, was immediately to be opened freely to the people of Cincinnati. And this expectation has been so much exaggerated and thrust forward by those who undertake to inform the public, without ascertaining the facts, that much disappointment has been created, both at home and abroad.

The plain truth is, that at no time yet, has the endowment, intended by Mr. McMicken’s will, been adequate, either in amount or stability, to sustain the two colleges which he designed…"

The Bellevue incline with UC's building in the foreground. [via CincinnatiViews.net]

Things existed like this for a long time—nearly two decades. In 1885, Jacob Donelson Cox was named UC president. He wound up being a driving force behind making UC the place that it is. One of his first orders of business was absorbing smaller schools into the UC ecosystem, adding colleges specializing in medicine, pharmacy, and dentistry. To accommodate this aggressive growth, Cox negotiated with the city of Cincinnati in 1889 to move the university up the hill from the McMicken estate to Burnet Woods. Burnet Woods had been established in 1874 when UC was just four years old. The land was leased (and later sold) to Cincinnati by its owners, William M. Groesbeck and Robert W. Burnet, to establish a park in honor of Burnet's father (and Groesbeck's father-in-law) Jacob Burnet. (Jacob was the first president of Cincinnati College in 1819. That school later merged with UC in 1918, giving us the founding date we recognize today. It all ties together.)

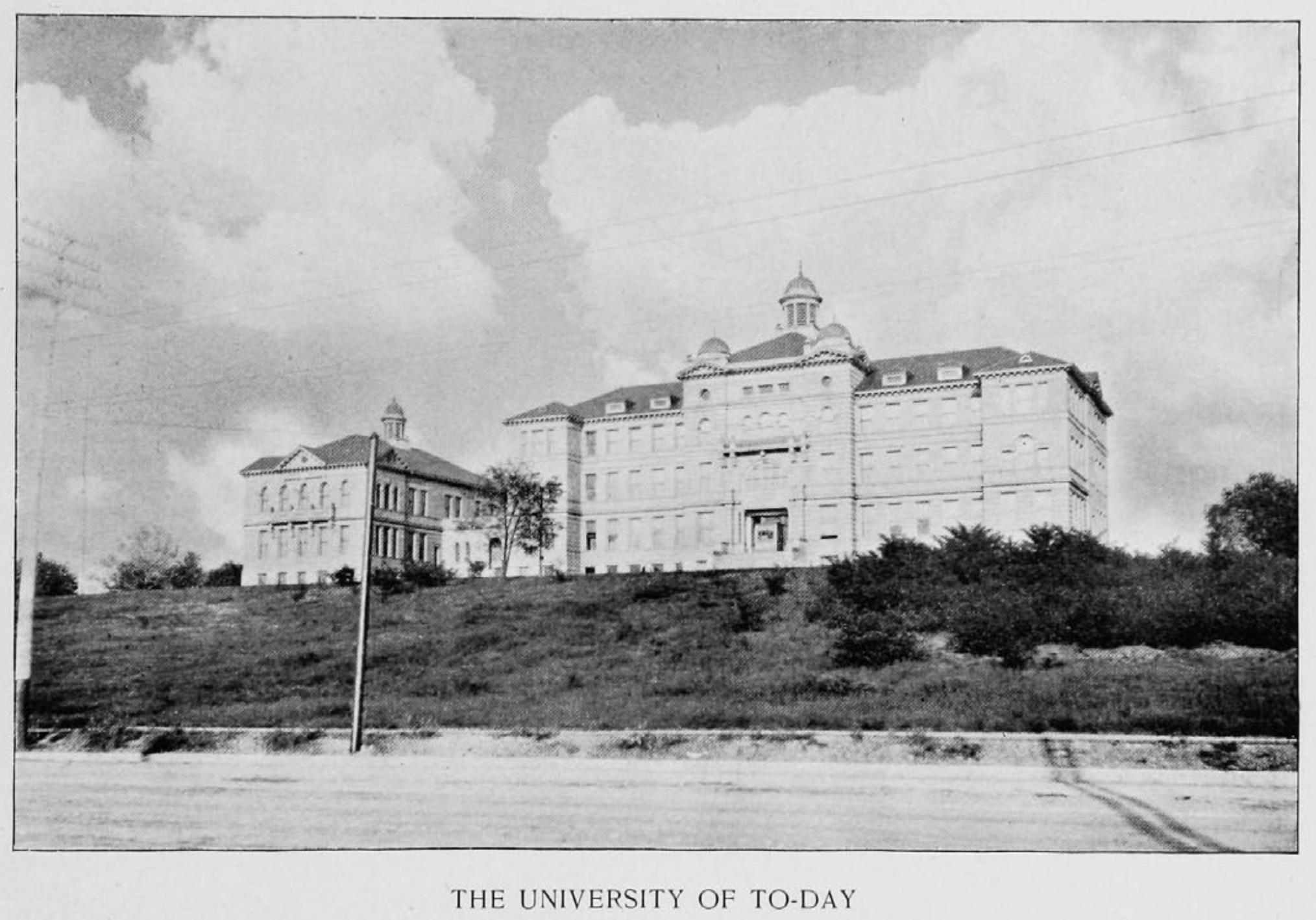

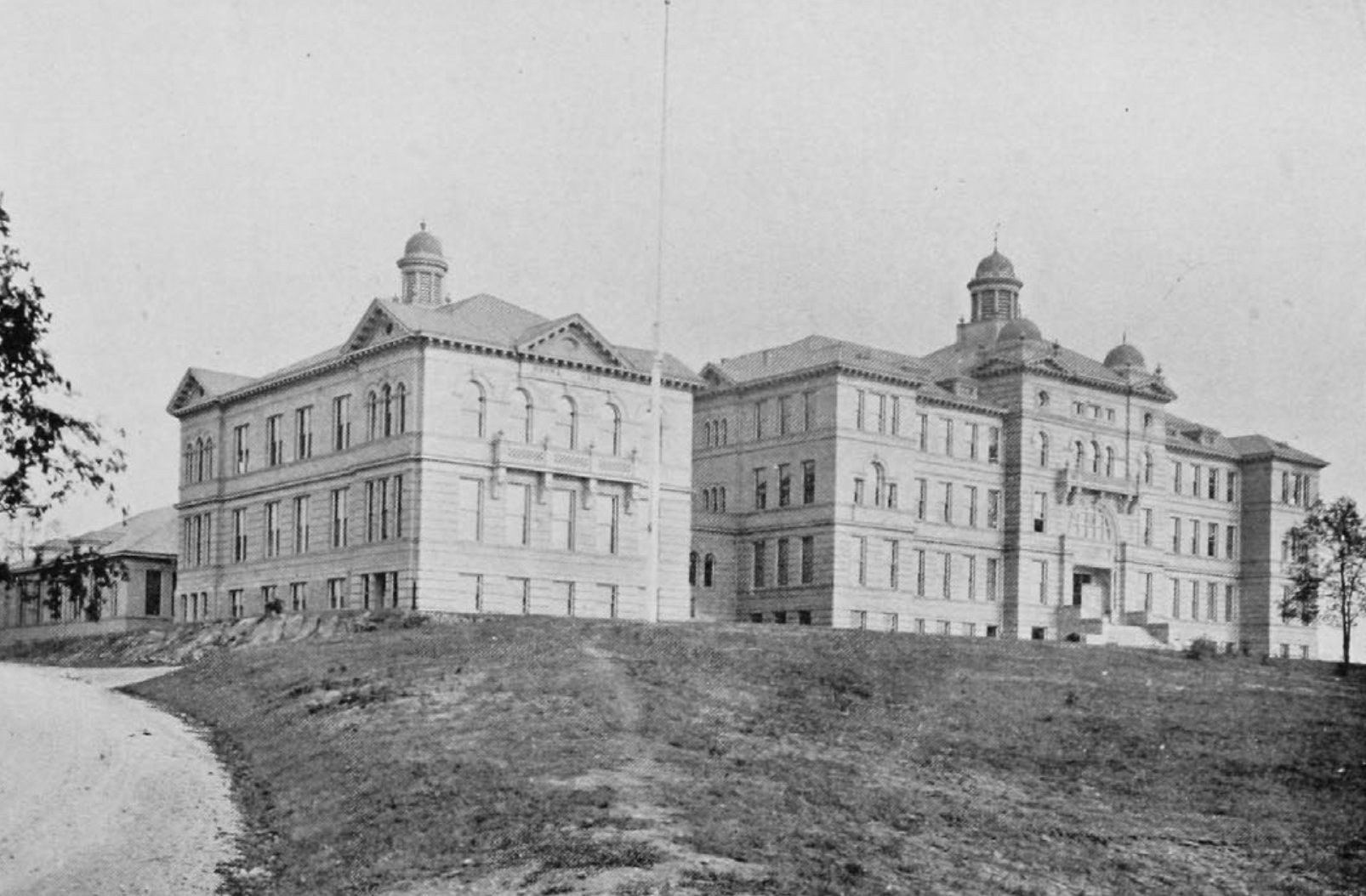

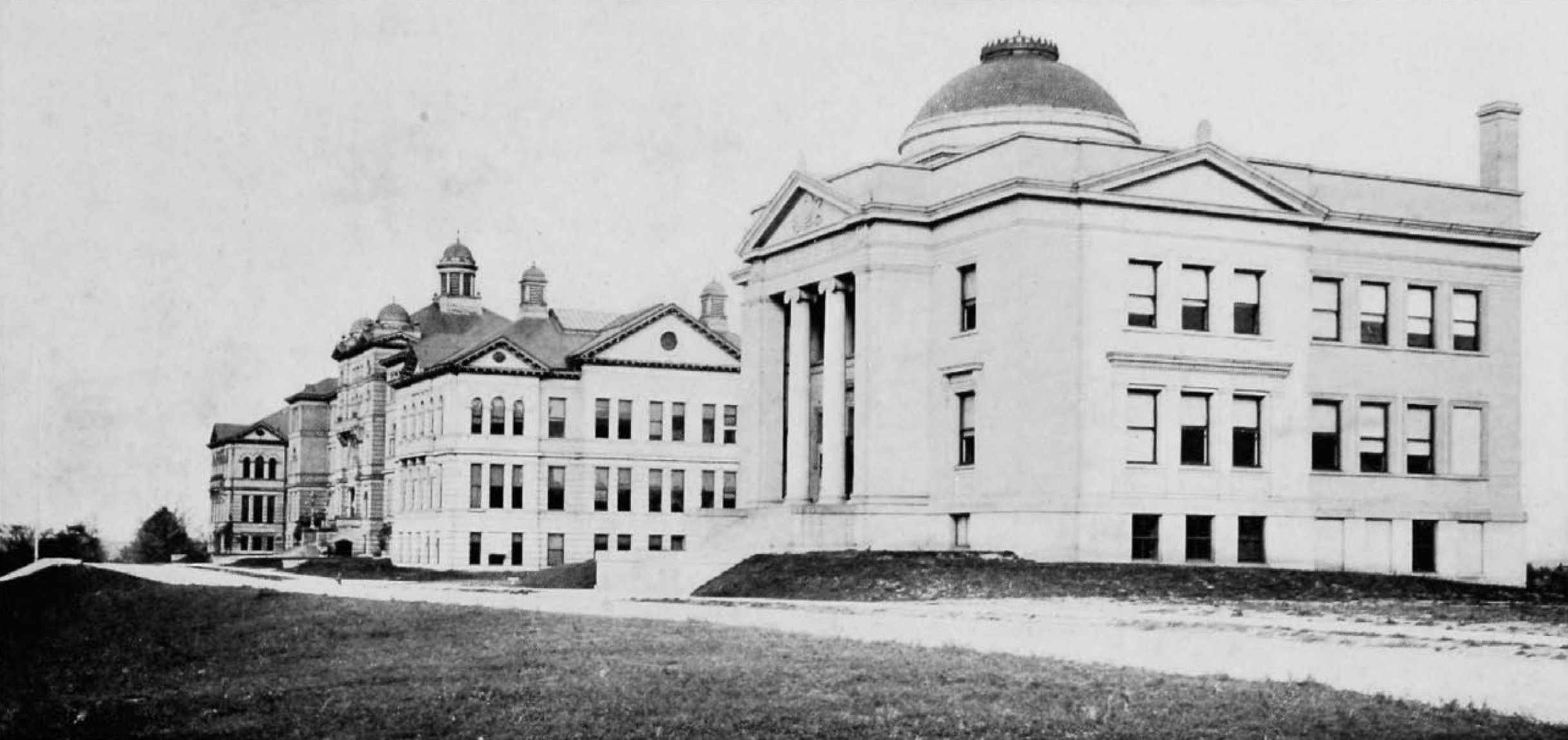

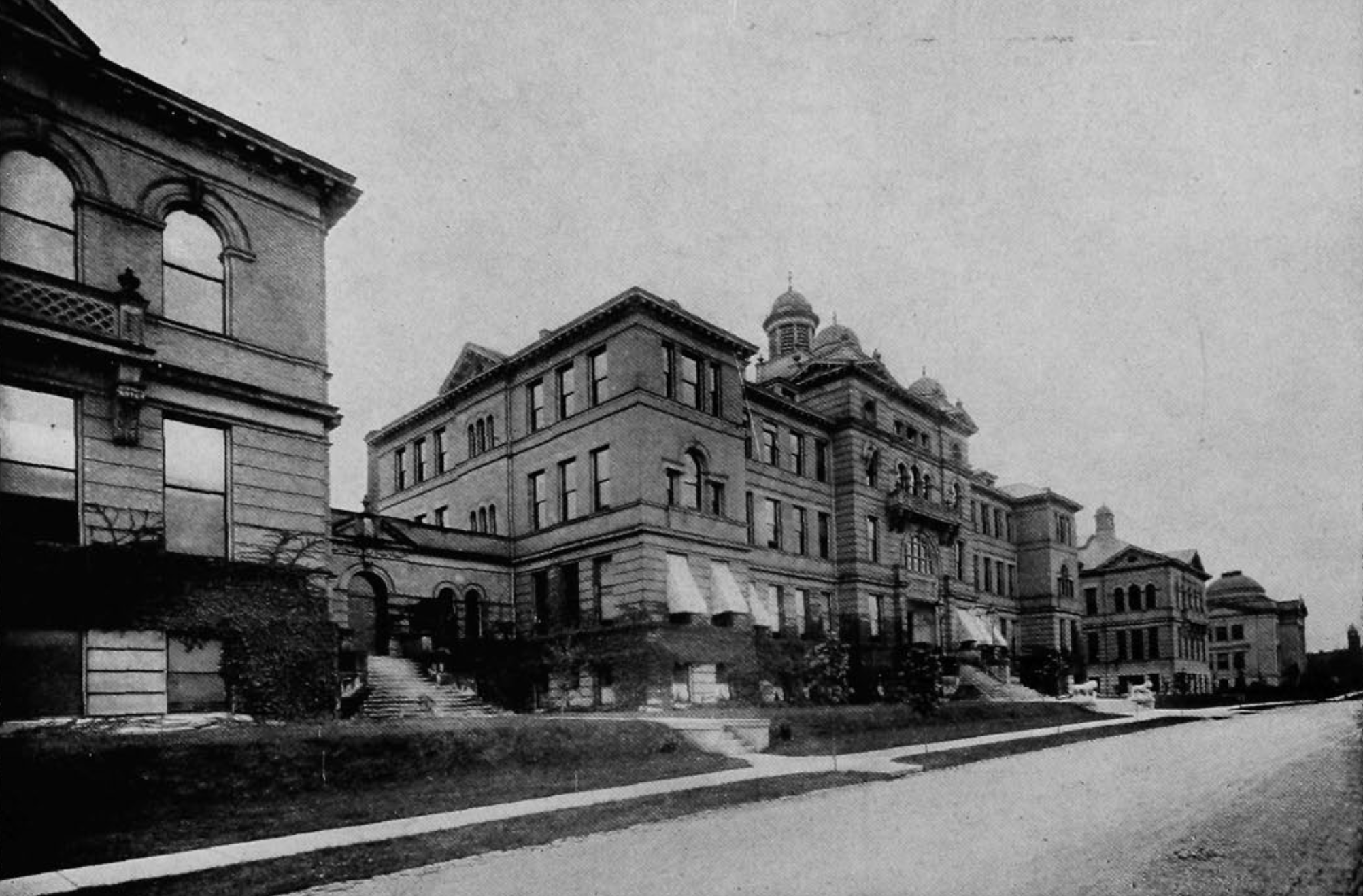

UC took over 43 acres of Burnet Woods for its new campus. At the time, the park stretched from Ludlow Avenue in the north (where it stops today) to Calhoun Street in the south. UC would take over the south end of the park, construct a much larger building to house the expanding curriculum and student body, and they’d name it after the university’s original benefactor.

Six architects submitted plans for the new site, which was to consist of the main building with smaller, connected halls on each side. Famed Cincinnati architect Samuel Hannaford won the job.

In 1894, McMicken Hall was born.

On September 22, 1894, UC held a ceremony to lay the cornerstone of McMicken Hall. There was an invocation by Reverend David H. Moore, followed by addresses by Cincinnati Mayor Caldwell, Alumni Association president Dr. Henry W. Bettmann, President of the University Directors Dr. C. G. Comegys, and General Samuel F. Hunt. They stuck a whole bunch of stuff inside the cornerstone: A copy of McMicken’s will, a copy of Matthew H. Thoms’ will, the first catalogue of UC, the most recent catalogue of UC, the 19th and 23rd annual reports, the mayor’s last annual message, the manual of the city, a copy of the Enquirer, a copy of that day’s program, a pamphlet “embodying the instructions to the architects of the building,” a copy of the Student’s Annual, a copy of The Cincinnatian (the UC yearbook), a copy of the McMicken Review (the student paper in the late 19th century), and the manuscript of Hunt’s oration: “Charles McMicken, Founder of the University of Cincinnati.”

On November 23rd of the following year, McMicken Hall hosted yet another ceremony. This time it was to dedicate the completed facility. UC had its campus. The total cost of McMicken Hall: $102,000—just north of $3 million in today’s money.

The ceremony featured pomp and circumstance. There was a “grand hallelujah song” by the Plum Street Temple Choir and a performance by the university mandolin and glee clubs. Comegys, a crucial player in the university's growth, delivered an address beneath red and black decorations. Mayor Caldwell also spoke, as did Building Committee member William Strunk.

(Sorry, another side note: Strunk was a UC alum who went on to teach at Cornell University where one of his students was E.B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little. Strunk and White later teamed up to write a definitive book that shaped writing education.)

McMicken Hall featured a Neo-Georgian style intended to align UC with other influential American universities. I can’t stress this enough, but the building was gorgeous and, I feel, much prettier than its replacement we use today.

![[photo via OhioPix.org]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527646048601-EGJ6RGH3C92K7KSFOP6D/p267401coll34_488.jpg)

![[via the 1926 edition of The Cincinnatian]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527977398064-16WXOLP4T8CODJJ9DW6V/McMicken.png)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527645750599-S0MFXSKRINL1IF55FD53/uc-d24.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527646606561-W7WMNUOITTDO0B77YQWS/UC-RP-dd.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527645747844-MQDUA1W87NSQ84G8WURR/uc-d1.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527645748960-9I9493W7QWDDKP19LAKT/uc-d23.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527645750548-PVEPSXB0CQU1R9NZEQ41/UC+McMicken+Hall+BW.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527645748127-E64ZC8636DHSA8TNLU4L/University+of+Cincinnati+5.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527646648796-F8HT4U2C3JP8AAXBJXR3/University+of+Cincinnati+9.jpg)

Serving as the heart of campus meant McMicken Hall had many duties. Among the first: Home of Bearcat basketball.

The crummy basement of the old building was the first place the 'Cats called theirs, way back in the 1900-01 season. The first recorded game took place the following school year as UC knocked off Engineers—a non-collegiate team—with a 42-21 final at McMicken on December 12, 1901.

It served as the home court of UC hoops for a decade and was a stage for some big wins over regional teams like Miami, Ohio State, and Kentucky. When Anthony Chez became UC's coach in 1902, he thought the program had potential if it could get out of McMicken. He claimed the cramped basement was as good for basketball as "a felt mattress for an oyster bed." Pillars blocked the playing surface, and the low ceilings rained dust and plaster upon the players when struck with a ball.

Despite the less-than-ideal conditions, the Bearcats would play there for a full decade, notching a 53-32 record before moving to a gymnasium (now known as Dieterle Vocal Arts Center) overlooking Carson Field in time for the 1911-12 season.

Mack in 1905 [via uc.edu]

On March 18, 1904, the university acquired a pair of lion statues from the estate of Jacob Hoffner, a successful real estate developer. Unlike McMicken—whose will purposefully left a gift to UC—Hoffner died of pneumonia in 1894 at the age of 96 and left everything to his wife. When Maria Hoffner passed in 1901, the interior art was to go to the Cincinnati Museum Association, and the exterior artwork (including the lions) were to go to the city, who would place them at Washington Park downtown or wherever they saw fit.

They were smaller replicas of the statues found in Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, Italy. When UC decided to place them on the front steps of McMicken Hall, they gave them names: Mack and Mick, in honor of Charles "Mack-Micken."

“Mack and Mick” was how they said it at the time, which I guess makes sense seeing as that's the order in which they appear in McMicken's name. Why, then, did we decide to switch the order? I think I have a possible answer.

When the lions first appeared on the front steps of McMicken, they faced inward. Because of this, the right-facing lion (on the left side of the steps) was named Mack, which came first in McMicken's name. The left-facing lion (on the right side of the steps) was named Mick, which came second in McMicken's name.

When the new McMicken Hall opened, and the statues were put back in front of the building, they decided to switch sides, facing outward like they do today. Suddenly left-facing Mick was on the left side and right-facing Mack was on the right. Mick and Mack.

(Again, I don't honestly know if this is the answer, and some continued to call them Mack and Mick after the change. However, I've never heard an explanation, and this seems very plausible.)

Private William B. Fleming in front of the original McMicken Hall, 1943 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]

McMicken's final calling came during WWII when UC used it for barracks. At its peak, the complex—including adjoining Cunningham and Hanna Halls—housed 2,450 soldier-students from the Army Specialist Training Program. The program overtook the facility in aggressive ways, even hijacking The Glee Club's room, renovating it to use for showers. (Rest assured, they made jokes.) The last of the soldiers moved out in the summer of 1944.

It was around this time—and perhaps because of it—people began to realize McMicken Hall was falling apart. In 1944, UC president Dr. Raymond Walters took steps to alleviate UC's growing pains. He sought to add a new women's dormitory, citing a belief that many women from outside of Cincinnati had stopped applying due to lack of suitable living space.

Also on Walters' to-do list was addressing McMicken Hall. At this point, it was 50 years old and just wasn't up to modern standards. He called it "antiquated, ill-spaced for instructional purposes, wasteful as to space and hard to heat and light," saying "a modern building to replace it would be an economy in the long run." In 1948, a university employee would write a letter to the Enquirer supporting this decision to raze McMicken:

"True, the brickwork is still in fine condition, but otherwise there are only the doors that are in fair condition. Floors, walls and foundation are crumbling; the window frames are decayed from heavy rains and snows. Plumbing very bad, that is the old plumbing. Steps leading to first floor of McMicken Hall in poor shape. The lions may weather a few more years, say 10 or 15 years more or less."

Incorrect predictions about the lifespan of Mick and Mack aside, UC agreed with this assessment of the building.

President Walters proposed a post-war renovation plan that included $1 million for a new McMicken Hall. By January 1945, he chose an architect: Cincinnati's Harry Hake. He'd rebuild McMicken in a similar Georgian style to the original.

Preliminary sketch, April 1945 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]

World War II ended in September 1945 and UC began to get serious about replacing McMicken. Unfortunately, by December 1947 when the university finally got around to making formal plans, building costs had skyrocketed, and the original $1 million projected price tag of the project had surged to more than $1.8 million (about $20.2 million in 2018). The university elected to cut costs by repurposing 650,000 bricks from the original building—just like the one that UC alum Joseph Strauss infamously incorporated into the Golden Gate Bridge. They'd start in April and shoot for an 18-month timeline.

On April 7, 1948, Mick and Mack were put into storage and construction on New McMicken was underway.

Old McMicken demolition [The Cincinnatian]

Old McMicken demolition [via The Cincinnatian]

McMicken Hall under construction, September 1948 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]

Of course, not all were so happy to see the original McMicken go. Another UC faculty member wrote to the Enquirer just before demolition, expressing frustration at the lack of an ability to explore renovation options. He said he "respectfully requested the City Solicitor to secure an injunction in order to allow non-university architects and engineers to estimate the cost of modernizing these buildings" but was refused.

One citizen, seeing the building's existence as more of a romantic than a practical one, sent a full-blown love letter to the Enquirer. It's a lot, but I must admit that it's beautifully written:

"'I look to the hills from whence cometh my strength.'

Every morning when I get up I look to the south through my 'picture' window toward the University of Cincinnati, Hebrew Union College College and Good Samaritan Hospital. Institutions of learning and the healing arts, which act like medical castles atop a wooded, green carpeted hill.

This is an inspiring and soul lifting view to one who formerly trod the halls of such-like houses of learning and healing, but who now is living in a wheel chair.

I never tire of looking at the tower of McMicken Hall in its ever changing setting just above the treetops. On clear days the whole tower stands out, shining bright in the sky. On cloudy days with an ever-changing background of floating clouds it is a television.

Sometimes, late on a cloudy day, the sun breaks through low in the west and shines for a few minutes on the gilded top-most tip of the spire on the tower making it look like a big star or a golden ball dangling in the sky.

Then as dusk comes on and deepens into night the windows of the tower begin to light up, making it a lighthouse for the surrounding countryside, reminding all of this center of learning atop this Mt. Olympus girded around by Cincinnatus.

But for me, the most beautiful view of all is on a foggy morning when one has to strain their eyes and look long and hard to make out the dim form of the tower in the fog to be sure it is still there, and then watch it become gradually, more and more visible. As the fog lifts and melts away and there it is, bold and firm pointing toward heaven as though inviting the children of learning to look to God for guidance in the preparation for their lifework.

While looking toward this man-made tower my every prayer is that man will cooperate with God in helping to preserve our civilisation and that all may learn that "We are our brother's keeper" and that we may be good-keepers and not keepers of war and bombs of destruction and hate, but truly keepers of the brotherhood of man through the fatherhood of God."

McMicken Hall under construction, May 1949 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]

McMicken under construction [The Cincinnatian]

The building wasn't quite done but was suitable to hold classes when the 1949-50 school year began. On September 21, 1949, New McMicken was up and running; construction workers be damned.

Alumni Association president, UC president, Student Council president and Building Committee Chairman pictured at the McMicken dedication ceremony, April 1950 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]

"We just started right in on our work," College of Business Dean Dr. Francis H. Bird said. "There was no time for speeches or dedicatory exercises." He did admit that the building was "a very fine place with excellent conditions for teaching" and complimented the acoustical, lighting, and blackboard arrangements.

On October 13th, Mick and Mack returned (in their new positions).

The following April, the new building was formally dedicated.

I must admit that I began writing this article hoping to frame some type of argument that the original McMicken should've somehow been preserved. While New McMicken is certainly beautiful (I even proposed to my fiancée in front of it), something about the original has always struck me.

However, it seems like nothing could've been done to save it. Late 19th-century building standards are a far cry from what we have today, and I think it says something that even replacing it with something up to snuff in 1950 meant a new building that was nearly 600% more expensive than the original.

You have to admit though, the place UC came into its own looked pretty special.

The original McMicken Hall [uc.edu]

![The original McMicken Hall [uc.edu]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527649952819-RFYX15VYX57YWPUPUAHA/McMicken+copy.jpg)

![The original UC building (circled) was located on a hillside next to the Bellevue Incline, pictured here in a promotional lithograph from Christian Moerlein Brewing Co. [via uc.edu]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527641443446-VLA59A5SE0MHG8CJ0DJB/original.jpg)

![The Bellevue incline with UC's building in the foreground. [via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527646906505-HI5TW1KLICA9KIMII0NO/Bellevue_Incline_1.jpg)

![[photo via CincinnatiViews.net]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527646447975-F9ZS6CFD3VRLV9V7L00Z/Entrance+to+Old+McMicken.jpg)

![Mack in 1905 [via uc.edu]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527702664666-6T9HLCI8032U6JP8ZR2J/1397059683326.jpg)

![Private William B. Fleming in front of the original McMicken Hall, 1943 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527973056714-M7N2CRJBR1MK6E664KIX/The_Cincinnati_Enquirer_Sun__Nov_7__1943_.jpg)

![Preliminary sketch, April 1945 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527973340962-OW0SDMCUFVJX07ICC0JR/The_Cincinnati_Enquirer_Thu__Apr_19__1945_.jpg)

![Old McMicken demolition [The Cincinnatian]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1528063778307-4E7F1ABC7JQ8MSPTY31D/Screen+Shot+2018-06-03+at+6.09.01+PM.png)

![Old McMicken demolition [via The Cincinnatian]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1528063484275-W3UR5M6VQ1HQA4MYAWD0/Screen+Shot+2018-06-03+at+6.03.48+PM.png)

![McMicken Hall under construction, September 1948 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527974095255-AGSKTJXP673LINOFMIRC/The_Cincinnati_Enquirer_Fri__Sep_24__1948_.jpg)

![McMicken Hall under construction, May 1949 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527975558117-T8X2EC6ECKQPQ2VKG85Y/The_Cincinnati_Enquirer_Sun__May_8__1949_.jpg)

![McMicken under construction [The Cincinnatian]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1528063630896-ABM9LIIL94FXZIJ9YFOE/Screen+Shot+2018-06-03+at+6.06.43+PM.png)

![Alumni Association president, UC president, Student Council president and Building Committee Chairman pictured at the McMicken dedication ceremony, April 1950 [via the Cincinnati Enquirer]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527976215747-GXMBONU0TIZTO8YVX6VM/The_Cincinnati_Enquirer_Sat__Apr_29__1950_.jpg)

![The original McMicken Hall [uc.edu]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1527646329215-4A57Y72WBT9VS3GHG0TL/1444158333470.jpg)

![University of Cincinnati’s home from 1875-1895, next to Bellevue Incline. [photo taken in 1906, Detroit Publishing Company] #Bearcats](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1563207714132-SOSY9OKXDG55TJA5QUN8/image-asset.jpeg)

![November 18, 2006 | Mark Dantonio and the Bearcats take down #7 Rutgers. [photos: gobearcats.com]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1560900133221-TRO20CHJZH0OWJX5DEYC/image-asset.jpeg)

![Semi-annual ‘90s (pre-Jordan) uniform appreciation post. [via Getty Images - bonus ‘96 Paul Pierce on slide 2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a2c2b4790bcce55e3166a34/1560452066508-T0JQQKVXCVY9N0G9RLUD/image-asset.jpeg)